The following post comes from Dr. Nicola Searle, an economist who specializes in the economics of intellectual property and the creative industries. This post is derived from a paper that Dr. Searle prepared for CPIP’s Sixth Annual Fall Conference.

By Nicola Searle

By Nicola Searle

The last two decades have made for interesting times in the media business. With rapidly changing technology, the digital era released content from the confines of physical formats and introduced a dazzling array of formats, channels, and other key elements of business models.

Business models describe how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value; business models have become increasingly important for companies to adapt to, and harness the opportunity arising from, the digital ear. In digital media, this transformation has been coupled with changing consumer preferences and delivery mechanisms, leading to increased copyright infringement. Unsurprisingly, copyright is a focal point of regulatory discourses in the digital media industry. A key theme has been the interaction of copyright and business models.

Thanks to support from CPIP, I have developed an in-depth analysis of the copyright-business models narrative in the digital media industry. My research uncovered different viewpoints, types of business models, and the existence of an unacknowledged theme in these debates: the legal business model.

Two contrasting perspectives on copyright policy-business models emerge from the research: the first, as in the quote below, where copyright is a fundamental legal tool to support the industry’s business models and the fight against infringement. This view argues that without copyright protection, digital media business models will fail. For example:

A second view suggests copyright law restricts business model innovation. This take often cites the wild-west of the early Google business model, and its relatively liberal approach to copyright in the United States, in contrast to more restrictive jurisdictions, such as the UK, where business model innovation has been relatively tame. It is demonstrated by this quote:

The question then is, does copyright hinder or enable business models in digital media? The answer is that is not the question. This debate is not about business models—it is about the legal business model.

My analysis of over 300 documents from the UK digital media industry identifies a latent concept in these discourses: the legal business model. The discussion is not about business models as such, but as business models viewed via copyright—which I term “the legal business model.”

In a traditional concept of business models, the focus is on value creation through goods or services. In the copyright-business model narrative, the “business model” is actually the legal model shaped and sustained by external legal structures (copyright), where regulations (copyright) create and protect value. It is a subtle difference, but it explains why UK copyright regulations to encourage business model innovation have not been successful and why copyright does not actually feature heavily in the descriptions of business models.

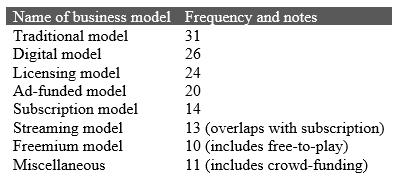

The research identifies various, yet inconsistent, labels for business models, as listed in the table below. The most cited is that of the “traditional model,” namely a model where content is sold directly to the consumer. The “digital model” is very similar—perhaps a digital equivalent of the sales of physical products. Other models talk about delivery and price mechanisms; however, only one business model is directly related to copyright—the licensing model. Only 16% of the business models mentioned in the sample are based on copyright; all the rest are framed instead around elements of the traditional concept of the business model.

In contrast to the drama and dynamism of the digital era and its copyright narratives, business models in digital media are surprisingly stagnant or resilient, depending on the perspective. The core model has not changed. For example, the CEO of Phonographic Performance Limited (PPL), a sound recording collective society in the UK, stated in 2017:

Other authors, such as Feng Li, have also found relative stability in business models in the sector.[4]

Coupled with a further analysis of the discourse, details available in the paper here, a paradox emerges. While copyright-business models insist on a strong link between the two, in practice the industry’s own framing and use of business models downplay copyright. The legal business model offers an explanation: the narrative is copyright-legal business models, not copyright-business models.

Yet, the stability of the existing business models and structure of the industry are not given. Market power has shifted to large technology platforms and gateways, and tensions have emerged. As streaming services that license-in content, such as Spotify, grow, they become increasingly dependent on external content owners. Services such as Netflix and Prime are now content creators, and content creators themselves are launching their own services, such as Disney+. Platforms have also been criticized, as described in the following quote from UK Music CEO Michael Dugher:

Business models and copyright continue to play a part in both regulatory narratives in the industry and the future of the industry itself. However, discussions thus far have not been a true engagement with copyright and business models in the traditional sense—only with debates over the legal business model. Perhaps the correct question is, should business models adapt to copyright, or should copyright adapt to business models?

To read the paper, please click here.

[1] Alliance for Intellectual Property, Trading Places: The UK’s IP Future, at 60 (2017).

[2] PricewaterhouseCoopers, An Economic Analysis of Copyright, Secondary Copyright and Collective Licensing, at 51 (2011).

[3] Phonographic Performance Limited, Annual Review, at 6 (2017).

[4] See Feng Li, The Digital Transformation of Business Models in the Creative Industries: A Holistic Framework and Emerging Trends, Technovation 92-93 (2020).

[5] See Chris Cooke, Music Industry Comments on Copyright Directive Ruling, Music Business Worldwide (July 5, 2018).